“Successful outdoor observation is not about possessing extraordinary skills, but about choosing to notice certain things when others do not” (31). ~Tristan Gooley

On the evening before a backpacking trip, my friends and I like to car camp near the trailhead. This allows us to get an early start without having to drive in the morning. I love the ritual of car camping because it adds a party to the start of the trip and gives you a chance to settle into full vacation mode. Being our designated driver, I settled in behind the wheel while the three women I was going to backpack with cracked a Pabst Blue Ribbon and got an early start to the party as we drove east from Bellingham, Washington to the Alpine Lakes Wilderness. My three friends, whom I had met while we all worked at an independent bookstore, were already slightly drunk when I pulled into the campground. Usually, I would have wanted to slam a few adult beverages to get caught up on the party, but for some reason all I wanted to do was sleep. By the time we set up camp, I was not feeling well, but I dismissed feelings that something was wrong. After all, I had had a pretty rough week at work. I didn’t want to complain because I didn’t mind the drive, and I felt like I could easily blame my exhaustion on work.

That morning before picking everyone up I had just finished grading 125 essays written by college freshmen who either resented having to take my class or they half-assed my course so they could free up their focus to pass college algebra. One blessing about the end of the term was that I did not have to write comments for revision. The cycle of revisions could end for both me and my students with the quarter ending. Clicking “submit” on their final grades signaled the end of the term and the beginning of my time off. Albeit unpaid time off for adjunct faculty. I loved how academics call this time of unemployment with a euphemism of being “off contract.”

At that point in my career, I was a new teacher, so the days leading up to this trip were hectic. I was learning how to be a teacher on the job with very little support. An exhausting experiment of learning as you do the job. What might have worked in one class would also fail in the next. The constant stress of whether or not I had a job wore me down. The pace of finishing the term was a sprint to submit final grades. Explaining to students why they failed or how they could recover from their first A- was one of the many things that made teaching hard and exhausting. In the 48 hours after submitting grades, I would nervously check my inbox for messages from the dean who would contact me if there were student complaints. I dreaded having to talk to deans about student comments from people who did not like me and/or my class and I also never knew if my contract was going to be renewed. If there were no emails, and the voicemails were silent, I would begin to breathe, write my out of office message, and set out for adventures.

I dismissed this exhaustion because I thought it was my incredibly stressful job. I was getting older, after all. A ‘woman of a certain age,’ I was. I never once considered something may be wrong with my body; it seemed like there was always an environmental factor where I could settle the blame. Never occurred to me that getting older was not just something that happened to other people; it was happening to me.

When I settled into my tent and zipped up my sleeping bag, I could hear my friends laughing about something with my name punctuated between fits of laughter. My most enduring friendships, the long-lasting ones, are with people who can sustain a joke by constantly one-upping each other. A banter which only seems to improve over time. Smart-asses, people who use puns easily, and anyone who can tell a good joke are my kind of people. As I zippered up my sleeping bag, I could hear laughter sustained by stories, the cracking of beers, and the lighting of cigarettes. I relaxed into my sleeping bag, and all I had to do was backpack instead of thinking about the stressful job of teaching.

Once or twice, I thought I could hear them yelling my name and expecting an answer, but the pounding in my head felt more intense, as I rolled over in my sleeping bag and disappeared into a heavy sleep. As my eyelids got heavier and my head began to pound, my ears felt like I was underwater, and my eyes were on fire. I pushed down the thoughts that something was not right with the way that I felt.

In the morning, I learned they were in fact calling me, making me the butt of their jokes. When they did not hear a response, their laughter escalated. They were making fun of me for retreating into the tent alone so I could “swirl the pearl” or play with my “button.” Various masturbation jokes went on from there, one friend outdoing another friend’s dirty joke which lasted for hours punctuated by the opening of IPAs. I laughed along with them over the morning coffee even though my head pulsed and ached. Inwardly, I was really starting to feel awful. Like I was coming down with something. It surprised me that I hadn’t heard a word of their banter because I had slept really hard through the night.

As I listened to the jokes over coffee the next morning, they wound themselves into fits of laughter again with a new audience about the self-pleasure jokes. We boiled water for coffee, while they helped one another remember who said what, when, and why. I laughed along with them as my cheeks flushed listening to the dirty things I did not do to myself. As I smiled, I felt a tightness and crusting of my right eye, and the massive headache I felt growing in my temples hurt when I laughed too hard. The headache had grown in intensity overnight, and I chalked it up to dehydration or possibly the lingering effects of a hangover from drinks the night before we left for this trip, as a pre-funk to the actual trip.

After cleaning up camp and taking one last inventory of our packs, gear, food, and water, I took my place in the line as the last person with the shortest legs and thus the slowest pace. We hit the trail enroute for our first backcountry campsite sometime close to midday. None of us wore a watch, and this was the pre-cell phone era for me. I’m pretty sure we wanted to live in the moment, but I now think it’s a good idea to have a watch and a way to tell time. Somewhere along the way a hiker who passed us called us a “Lady Train.” I decided right then that if we were a train, then I was the caboose. On this Lady Train trip, we were walking to a high-country campsite above the treeline, and we had a schedule of permitted destinations to follow. We had to keep a particular pace, our permits kept us on a schedule even though we were technically going off the grid. We were getting away from it all but we still had to keep an eye on the schedule. The Lady Train still had certain stations to arrive on time, if you will. Despite not having a timepiece, we did have a plan for each day and the long Pacific Northwest evenings where the sun set close to 10pm made it easier to enjoy the day. We were heading to a pristine backcountry where you had to apply for a lottery to secure a campsite. We had to get to our permitted spot on time, or we would lose our privilege to the site, and somebody who had arrived already could take over our spot in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness.

It was a camp spot straight out of a Patagonia clothing catalog, which for years was my city girl’s shorthand way of describing a beautiful backcountry place. I had no other reference point with my city life. When I lived with my parents in suburban Atlanta as a teenager, the Patagonia catalog used to provide me with hours of daydreaming about places I would like to go and the fancy outdoor clothes I hoped to one day afford. I was beyond elated that we were on our way to one of those places I had bookmarked in my catalog of sites in the North Cascades National Park. Aside from me, the Lady Train had all grown up in the Pacific Northwest, so I kept my giddiness of going to catalog destinations to myself. They appreciated the beauty of this area, no doubt, but they were no longer gobsmacked the way I was when I saw blue-green water or trees larger than the width of cars. They often looked at me like I was silly when I shared my suburban awe.

At the start of the trip, we had cloudy skies, and there were some heavy gusts of wind from the north, but it was nothing out of the ordinary. By and large it was a pleasant hike for our first night away from where I had not pleasured myself in the tent while my friends got wasted around the campfire. Once we got to our site, my right eye also felt dry and crusty. My right ear felt clogged, like half of my head was under water.

While I was hiking, I did not think too much about my head because I was carrying close to fifty pounds on my back. My leg muscles, joints, and bones were screaming from the strain, and my lungs were pumping for air. The weight of a pack alone created a lot of suffering while walking the trails, so the constant state of bodily discomfort felt like a companion. I did not pay too much attention to my head until we stopped for a snack. Without my muscles clamoring and my lungs vying for attention, I felt a drum-thrum-thrum-drum-thrum in my head. An uncomfortable pressure bloomed just behind my right eye.

When we finally got to the top of the highest pass, I looked down at the camp in the ravine where we were going to sleep for the night with its beautiful kidney-shaped lake and green lush pine trees. Usually, I like to pause and savor the accomplishment of climbing to the high alpine, yet all I could think about was getting into my sleeping bag. Instead of enjoying the view, I started to day dream about where I would set up my tent. Thoughts of laying down in my sleeping bag set me off into a series of yawns. I was exhausted, and my early retreat into the tent last night felt like a long time ago. I did not want to alarm my friends about how I was feeling, so I nonchalantly asked one of them if my eye looked weird.

There was instantly a look of alarm on her face. My heart sank. Her eyes got wide. “Holyfuck. What is wrong with your eye?” she said as her hand flew to her mouth as she shook her head.

Damn, I thought. I look as bad as I feel. Not a good sign.

She asked if I wanted to see her compass mirror to take a look at my “unnaturally red” eye.

I decided it was not a good idea for me to inspect my eye just yet. Her reaction confirmed what I could feel; something was really wrong based on how feverish my head felt and by the way it was pulsing. I started to think about if I could manage to keep my face clean, things would work out okay. I would heal in the mountain air, and the crisp clean waters of snowmelt would be just what the doctor ordered. I held firm to the theory that my teaching career was the cause of my fatigue. This tactic, of trying to dismiss a gut feeling about my health, it turns out, created a little world of private suffering and paranoia. My fantasies about laying down in my sleeping bag kept me walking forward with a heavy pack on my shoulders silencing my legs and lungs. After we arrived at the camp, I decided to take some time alone by the dark green lake and clean my face.

As I sat on my foam seat pad and wet my Cool Rag, the bandana that I had packed for this purpose. I tilted my head to shake my ear. The whole right side of my head felt clogged up, my headache had gotten worse; I knew I was on my way to experiencing the kind of ear infection I got as a kid when I got to swim in the public pool.

I recognized the feeling of what was happening with my ear as similar to “swimmer’s ear,” but the eye condition was something altogether new. I pumped drinking water and guzzled an entire water bottle of freezing water hoping I could solve my problems by pretending this illness was dehydration. The lake water was refreshingly cold and I pumped about four gallons, enough for all of us. I settled on using a lot of my Doctor Bonners’ soap to clean my face. The peppermint scented soap usually feels refreshing when I am bathing or washing my hands. Tingly and cool, that hippy soap. Now that I was not feeling well and fighting a possible infection on my face, however, it burned like pouring alcohol on an open flesh wound. As I washed my face, I held my head up to the wind and dried my eyes on my Cool Rag. I tried to put on a happy face as I walked back to camp. It was then another friend made a comment about my eye, and all three of them circled around my tired body to examine my pulsing face.

All I wanted to do was go to sleep.

The wind was really irritating my newly scrubbed face, and as the sun disappeared behind the ravine, the temperature dropped and I was getting colder. As I sloshed up the hill with our water containers, I saw my friends standing in a circle having a discussion as they smoked. When I arrived, my friends were looking at my eyes. I got the impression they had had a private discussion about my face while I was down at the lake. They also noticed how quiet I had been all day as I was in my world of hurt. This time, I was not the focus of their jokes, but of their sweet concern. I tilted my face towards the pinkening sky and I could see the branches of the trees swaying on the pass as my eyes watered. Several layers of clouds swirled, darkening the sky. The weather was about to change, and a cold mountain night descended upon us as the golden alpenglow faded.

One of the beautiful things about camping at elevation is the views and the solitude from other people. The suffering you put your feet and legs through is worth it in the time between dusk and the night. Ideally you want to enjoy as much of the time as possible because it is so precious and rare. These backcountry sites are hard to get to and it’s perfect time in the mountains. There was another tent at this site, but we had not seen any sign of a park ranger yet so it increased the serenity of being remote. What I had always imagined a Patagonia catalog site to be.

The comfort you sacrifice for the glory of being at this elevation, however, is the warmth of a campfire. In Washington State, it is illegal to make a fire above 5000 feet and as the forest fires of climate change become more of a part of our lives, there may even be burn bans altogether. You have to make do with whatever clothes you have or call it an early night and get into your sleeping bag. Or freeze.

Another challenge with backcountry hiking is the forecast can change and you have no way of knowing about it without a satellite radio. Having felt short strong gusts of wind all day, I could sense the weather was about to change. Our night without a fire would prove to be windy and possibly very cold. The temperature felt lower than my three season bag was designed for, so when this happens you feel your body heat escaping through the zipper of the bag. So you have to add layers of clothes to protect your skin. The fireless mornings are harder and the tent is very difficult to exit even if you are in the scene of a fancy outdoor catalog. The weather becomes another companion on the trail.

The winds continued to gust and grow stronger, and this irritated my eye further. I took to wearing my sunglasses at all times to protect my left eye since it was still working correctly. The glasses also helped protect the crusting pulsing eye, so this helped my morale even if I looked silly on the sunless day. I pushed my worries down as I packed and felt my head pulse.

My friends took turns investigating my eye, and their concern started to get on my nerves. I preferred to suffer in silence; I could not manage anyone else’s anxiety while I struggled to comfort myself. I figured the less said about it, the more they might leave me alone. The concern on their faces mirrored my growing anxiety. Having a fair amount of trips under my belt, I had experienced a lot, but I had never been ill in the backcountry before.

That night, I laid there feeling my head pulse, and every time I rolled over, I could feel mucus and liquid in my head drain from one side of my sinuses to the other. My ear felt clogged and crusty, and my eye burned. My nose felt raw, and it would stop running. My Cool rag was drenched from wiping my face. No doubt I was very sick, and I convinced myself I had an eye infection and that the ibuprofen I took would clear it up after I got some sleep. I zipped up my bag tightly under my nose and pulled my head inside the bag. I felt like I had wax in my ear, and that I heard everything through a tunnel. My eyelashes had laced together with a gross hard crust that felt like superglue. I was like my ears and eyes were full of gauze.

The wind continued to howl over the ravine.

When you are camping at elevation, above the treeline, you can hear the wind approaching for miles before you feel it. The sound travels across the tops of the trees, rolls over the hills, and then eventually hits your tent and rattles the canvas. Tent walls ripple like sheets flapping in the wind. It is a sound that builds in intensity like an on-coming train. There would be no sleeping on this night, I thought with dread and sadness.

When I woke up to the first light before dawn, the winds were gone. With one eye I could see the sky breaking through clouds when I peeked my head out of the screen door of the tent. My sore eye had crusted shut, so I used some cold icy water from a bottle nearby to soften my handkerchief that had frozen during the night. I rubbed my eye gently fighting the sad desire to be at home in my bathroom near all of my home first aid, soft clean towels, and mirrors. Fighting those feelings away was really important since I had been looking forward to this trip all year. I started to feel depressed that here I was, on an ideal trip with friends, and I had the misfortune of getting sick. I was going to make it, I decided. I had to buck up, but I felt like crying.

I sat down with my first aid kit to see if there was something that might help improve my situation before my the rest of my party woke up. My nose continued to run like I was sick, which at that moment, I decided to be honest with myself and admit the truth. I was sick in the backcountry; I had to face it.

Sorting through the various bits of cream packets, band-aids, and bandages, I found a small sample packet of Neosporin in my first aid kit. It was something I could put around my eye that could work like lotion which I desperately craved. I thought about how I could maybe accost fellow hikers for their supplies and possibly be saved on the trail.

Perhaps the kindness of strangers who carried face lotion could help? The thought of sharing eye drops seemed a bit gross. Not to mention who in their right mind would share their eye drops with a mess like me. Propositioning hiker strangers was a skill. I hit up some guy with dreads once who was walking towards me on a switchback and I asked him if he had a cigarette, and he said yes. He even stopped to roll two for me; one to smoke with him right then and there and the other for later as I had planned. We chatted a bit, did not introduce ourselves, smoked, and talked about our hike. Dready hiker was the best!

Would asking somebody for lotion be the same experience? Probably not. Might even be kind of creepy. This is what I had decided to fantasize about though as I rubbed Neosporin around my eyelids feeling hopelessly pathetic and sad for myself imaging the two bottles of eye drops I had back in my bathroom at home.

To this day, I always carry a small bottle of eye drops in my first aid kit. Having lived through this worse-case scenario, I feel like I need to make sure I don’t let this happen to myself again. My eye was so dry it ached. As my nose ran and lost moisture, I felt like my ear was also entirely clogged. With all of the tunnels, twists, and turns in my ear canals, there was something brewing in my head. You become hyper-aware of what you forgot to pack or what you had decided that you did not need to carry.

And that is the thing about packing for a trip, really. You can’t always carry everything you may need for the worst case scenario. You have to make peace as you are preparing for your trip. What you decide to take with you may be all you need, or you will have to accept you’re making sacrifices to save weight.

What you want to carry and what your shoulders can bear are two very different things.

Most people have had this experience in their lives when you are caught needing something you left behind, be it on a vacation or on your commute to work. When you are backpacking this mistake is pronounced by having chosen not to bring something in order to lighten your pack. With first aid, for example, you want to have the things that will either provide comfort until the end of your trip or what will sustain you until you can get the help you need.

In the case of my eye, some drops would have helped flush out whatever was ailing me, and I made do with rubbing the corners of my eye with the Neosporin. The whole process left me tired, and I gave the last of my whiskey to my friends. Slightly depressed that I felt so ill, I settled into an early night again for the fourth evening in a row after hiking all day. We were back down below the tree line so I listened to the crackling of the fire hoping the next morning I’d wake up feeling better. My friends were a bit more subdued, and I don’t think they made fun of me that night as they sat around the fire talking.

In the tent before falling asleep I felt a wave of depression and sadness. I felt sorry for myself that a week of glorious hiking was getting eclipsed by this infection. Instead of counting sheep, I listed the first-aid supplies that I would pack in my first aid kit forevermore. I would not make this mistake again. I also thought about the ring that I saw around the sun before the wind kicked up, and I remembered the different layers of clouds that had changed and altered throughout the day. The sky in the backcountry was always so interesting, even with a comprimised eye.

Once you’re in the backcountry, you have to use your best guess about the supplies you will need, and the one variable that can change quickly, like your health, is the weather. Since that trip, I’ve learned a few unreliable signs about the weather that I have gleaned from various sites on the internet. Self-taught meteorology is an art not a science. For example, a wispy circle around the sun is a clue that the weather is going to change but it might take 12 hours. Whether the change will be for the good or better is not clear; change is the only reliable factor.

I also learned some things by reading Tristan Gooley’s The Lost Art of Reading Nature’s Signs. When I picked up the book, I was immediately drawn to the watercolor drawings on the cover, and the promise of learning forgotten skills. The language of weather is really quite amazing poetry. I read couplets that will change your life in a minute. Here are a few of my favorites from “weather folklore” thanks to Gooley:

Oak before ash, we’ll have a splash.

Ash before oak, in for a soak.

High wispy fast moving clouds mean we’ll have a dewy morning.

Red in the morning, hippies take warning.

Red at night, hiker’s delight.

He also taught me beautiful words like “silviculturists” and that “some trees are gregarious and some anti-gregarious: beeches and hornbeam get lonely and love to group with others, whereas crab apple trees can’t the stand the company of other crab apples and prefers to grow away from its own kind” (46). I loved this idea that trees were a community, and I read his book from cover to cover like it was a mystery novel. Tristen Gooley, your brain is dreamy.

Years later after the eye infection trip, I was hiking with a trail crew and the leader had a satellite radio for emergencies and to get information about the weather. In order to get the best reception we could find, we needed to hike up to a pass. I thought this was extraordinary, so I offered to go on the mission while the other trail crew folks took the day off. I was physically exhausted from the trailwork we had been doing of cutting down a water-soaked log to improve the drainage of a creek, but I was really interested in being able to hear a nautical forecast in the backcountry. This was magic I had not experienced, and I pushed down the shame I felt when I thought of Gooley, who would have wanted us to look for clues in the hillside rather than using technology. To him, “the real fun come(s) when we bring the disparate ingredients together in a great fresh pudding of deduction” (3). Despite his poetry, I quickened my pace to keep up with the trail crew leader who walked uphill like a mountain goat.

We hiked up to the saddle of the pass above where we were camping, and he took out this breadloaf-sized walkie-talkie. He turned it on, some static brewed up, and then a robot voice gave us a forecast which delighted me to no end. We looked each other in the eye and raised our eyebrows when the weather robot told us about the changing winds and the chance of rain. We listened to the nautical forecast because the trail crew leader informed me that this way we could be prepared for folks who had trouble keeping their spirits up when the rain poured on trail crew outings.

“Some people,” he said, “suffer better than others.”

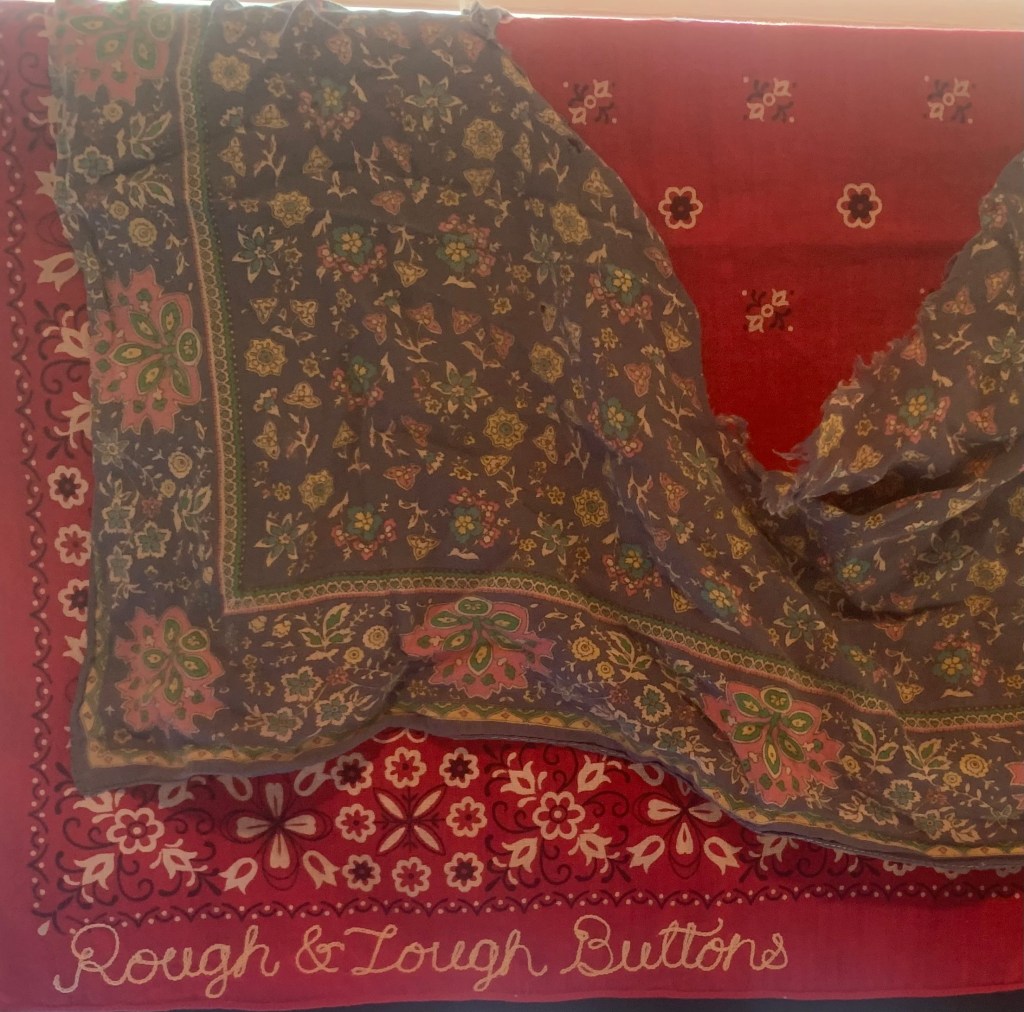

I did not ask, but I assumed he had some horror stories with the weather and trailcrew volunteers. I made a note to look up terms having to do with the nautical sunrise, sunset, tides, and the moon. My brain spun as we hiked down to camp. I thought back to my trip when I had the eye infection, and one of my friends complimented me on being so rough and tough. Somehow the “button” joke and my rough and toughness led to my trail name: Rough and Tough Buttons. My first trail nickname that she lovingly had embroidered onto a bandana.

Who we are when we suffer, it turns out, brings out our worst or our best. It’s like what the weather can teach us about ourselves if we’re open to it.

If you don’t like what you see and feel, just wait ten minutes.

Thanks for reading, and I know this needs work, but I’m sharing this since it’s been a lonely year on this blog. I have been working on finishing this book and learning how to watercolor, so I’ve backed down from public writing.

Some victories from the last six months:

1] I wrote my first poem in decades, submitted it, and got a rejection. They invited me to a reading to share my work (which was nice), but fuck that noise. I need practice speaking in front of people like a hole in the head.

2] I made a huge discovery of a memory that has liberated me from feeling like a failure with this memoir. Turns out I tore up the journal I kept when I was 18-20 because my then boyfriend read it without my permission. In a dramatic fit of tears and embarrassment, I tore it up as we argued. This book is that young girl inside me who wants to read those thoughts. I had a nightmare in the backcountry that was a replay of that night I had long forgotten. The menopausal brain is a fun house of horrors. Memoir forthcoming.

3] So now I know what this book has to become: it’s older me interpreting the lessons of younger me. Older me, who wishes she had not destroyed her work in a fit of rage, is still not sure if it’s a full memoir (a memoir). BUT I am aiming to have four pieces I can send out for publication by the end of the year. The other book I want to write is losing patience and I need to get the fuck on with it. I’m not getting younger. 2024 will be the last day of our acquaintance, dear memoir.

4] The death of Sinead O’Connor reminded me that I played her perfect break-up over and over and over as I drove away from a life I knew was wrong for me. Good Christ 56 is too young to die. I am so glad she was the female singer I looked up to rather than the complete shite young women have today. Bless their hearts.

5] I have been committed to writing during working breaks the last six months, and sometimes it’s trolling my husband on Insta, writing texts to friends, or writing in a journal I know my hubs would never read without my permission, and today it’s this blog.

Here’s the feedback I got about this work above from a brilliantly patient editor I’m working with, and I’m going to think on it as I walk into the woods this week:

I love this conclusion! But, as of yet, the story doesn’t quite support this closing thought. The material is definitely there to support this thought!! We don’t (yet) find out how her hiking trip ends, how she makes it back and how she feels about the adventure later.

We need to SEE her learn this lesson.

I know we do. A Memoir.